Main

Description

展廳8將由10月8日(星期六)起暫時關閉,以籌備於11月開放的新特別展覽。展廳8重新開放時間將於11月公布。

故宮博物院典藏的中國書畫精品,大部分都是國之瑰寶。它們受重視的原因,除因其非凡的藝術成就,亦因其豐厚的鑒藏史。本展覽精心挑選三十五件(其中有六開為一套冊頁)晉、唐、宋、元書畫,從藝術、文化、歷史等角度,探究它們千古流芳的原因。展覽共分三期,每期展出十件珍品,精彩可期。

按此購票入場

展品清單

第一期:2022年7月2至31日

- 王羲之(303–361)

行書雨後帖(宋臨摹本) - 米芾(1051–1107)

行書研山銘 - 趙佶(1082–1135)

雪江歸棹圖 - 趙黻(活躍於十二世紀中期)

江山萬里圖 - 李嵩(1166–1243)

花籃圖 - 佚名

溪山春曉圖 - 李衎(1245–1320)

四清圖 - 趙孟頫(1254–1322)

秋郊飲馬圖 - 黃公望(1269–1354)

天池石壁圖 - 倪瓚(1306–1374)

梧竹秀石圖

第二期 :2022年8月3日至9月4日

- 顧愷之(346–407)

洛神賦圖(北宋摹本) - (傳)虞世南(558–638)

行書摹蘭亭序帖 - 盧楞伽(活躍於730–760)

六尊者像(宋臨本) - 趙佶(1082–1135)

楷書夏日詩帖 - (傳)趙伯駒(活躍於十二世紀)

江山秋色圖 - 馬遠(活躍於十二世紀晚期至十三世紀早期)

水圖 - 佚名

盤車圖 - 鄧文原(1259–1328)

章草書急就章 - 趙雍(1293後–1361)、王冕(1287–1359)、朱德潤(1294–1365)、張觀(活躍於十四世紀)、方從義(活躍於十四世紀)

五家合繪 - 王蒙(?–1385)

夏日山居圖

第三期 :2022年9月7日至10月7日

- 謝安(320–385)

行書中郎帖(宋臨本) - 顧愷之(346–407)

洛神賦全圖(南宋摹本) - 歐陽詢(557–641)

行楷書張翰帖(唐摹本) - 阮郜(活躍於十世紀)

閬苑女仙圖 - 馬和之(活躍於十二世紀)

小雅鹿鳴之什圖 - 李迪(活躍於十二世紀)

楓鷹雉雞圖 - 李嵩(1166–1243)

錢塘觀潮圖 - 管道昇(1262–1319)

行書秋深帖(趙孟頫代筆) - 趙孟頫(1254–1322)、黃公望(1269–1354)、徐賁(1335–1380)

快雪時晴書畫合璧 - 吳鎮(1280–1354)

漁父圖

Additional info

Tabs

7 September to 7 October 2022

Ruan Gao (active 12th century)

Female Immortals in Elysium

Five Dynasties, 10th century

Handscroll, ink and colour on silk

© The Palace Museum

Many scholars consider this to be the only authentic work by Ruan Gao. According to the Painting Catalogue of the Xuanhe Reign, Ruan was a skilled painter who excelled at female figures. During the Northern Song dynasty, only four paintings by Ruan Gao entered the imperial collection, one of which had a similar title to this painting and was described as “enthralling”.

Depicting the Land of Immortals, the work is executed with fluid and dense brushstrokes. In the centre, female immortals recite poems while playing a string instrument (sanxian) near a dancing phoenix. To the right other female immortals clear a table. On the far left and right, three female immortals arrive either riding a dragon, a crane, the wind, or on foot. This configuration is rarely found on handscrolls, but appears on earlier bronze mirrors.

The painting entered the court collection in the Qing dynasty and was recorded in the Treasured Boxes of the Stone Moat, a catalogue of important works of painting and calligraphy in the Qing imperial collection. The Qianlong Emperor ordered the court painter Gu Quan to make a copy, which was later housed at the imperial palace in Shengjing (present-day Shenyang) during the reign of the Guangxu Emperor. The original was kept at the Palace of Established Happiness inside the Forbidden City. In 1922, the former Xuantong Emperor Puyi gifted it to his brother Pujie, which saved it from a fire that destroyed the Palace the following year.

The painting was donated to the Chinese government in 1958 and later entered the Palace Museum, making it the only institution in the world that houses a work by Ruan Gao.

Gu Kaizhi (346–407)

Nymph of the Luo River (Southern Song copy)

Southern Song dynasty, 12th century

Handscroll, ink and colour on silk

© The Palace Museum

This painting is based on a classic poem composed by Cao Zhi, a prince who lived during the Three Kingdoms period. The poem tells the story of a romance between Cao and the nymph of the Luo River, and inspired many works of painting and calligraphy, including a painting, possibly by Gu Kaizhi of the Six Dynasties period, that served as a model for later artists.

Among surviving paintings that illustrate the poem, this handscroll is particularly rich and complete. The continuous composition depicts many scenes in the poem, from the moment Cao Zhi and the nymph met until their parting. It features many details not found in other versions, such as the nymph picking pearls and feathers.

Most scholars date this handscroll to the Southern Song dynasty. The red-brown tones convey a peaceful atmosphere, and the figures are delicately depicted in a landscape formed by texture strokes and ink washes. Selected lines from the poem are written in square grids in the style of the Tang calligrapher Yan Zhenqing, which is typical of works from the mid-Northern Song or early Southern Song period.

The presence of the numerous seals suggests that the painting was highly regarded by various Qing emperors. It was stored in the Imperial Study and recorded in the Treasured Boxes of the Stone Moat, a catalogue of important works in the imperial collection. In 1922, the painting was removed from the Forbidden City by the last emperor, Puyi, who bestowed it upon his brother, Pujie. It was later owned by an antique dealer before it was returned to the Palace Museum.

Ouyang Xun (557–641)

Biography of Zhang Han in Running-Regular Script (Tang copy)

Tang dynasty, about 8th or 9th century

Album leaf, ink on paper

© The Palace Museum

Ouyang Xun was one of the “Four Masters of Early Tang”—a group which also included Yu Shinan, Chu Suiliang, and Xue Ji. An erudite scholar, his calligraphy was highly regarded by Emperor Taizong of Tang, as well as many of his contemporaries and later calligraphers. It was so influential that it was used as a model for the typeface used in woodblock-printed books of the Song dynasty.

The prominent Tang critic Zhang Huaiguan described Xun as “proficient in eight scripts”. Employed here is a mixture of his best-known regular- and running-script calligraphy. Although now recognised as a tracing copy that was probably produced by a later copyist, it is regarded as being on the same level with Ouyang’s authentic masterpieces. The calligraphy faithfully reflects his well-structured and elongated characters, executed with rigid and angular brush strokes. The text recounts the unambitious yet contented life of Zhang Han, whose biography merited an entry in the History of Jin.

The work once belonged to the Northern and Southern Song courts. Recorded in the Calligraphy Catalogue of the Xuanhe Period, it was one of the few works retained in the imperial collection after the collapse of the Northern Song dynasty and the relocation of the court to the Southern Song capital of Lin’an (present-day Hangzhou). It entered the Qing imperial collection during the reign of the Qianlong Emperor, and was kept in the palace until it entered the Palace Museum collection. Little of Xun’s original calligraphy survives today, even in the form of copies— this is one of only four tracing copies made after his work.

Ma Hezhi (active 12th century)

Illustrations to The Book of Songs: Songs Beginning with “Deer Call”

Southern Song dynasty, 12th century

Handscroll, ink and colour on silk

© The Palace Museum

Ma Hezhi, a native of Qiantang (present-day Hangzhou), was a renowned painter of the Southern Song period. His landscape and figure paintings were judged to be superior by both the Southern Song Emperor Gaozong and his successor, Xiaozong.

The Book of Songs, dating from the 11th to late 7th century BCE, is one of China’s most celebrated poetry anthologies. During the Southern Song dynasty, Gaozong or Xiaozong ordered Ma to illustrate 305 paintings for the anthology. Among extant examples, Songs Beginning with “Deer Call” is an undisputed masterpiece, distinguished by its elegant palette, calligraphic brushwork, flowing drapery, dynamic rocks, and meticulous architectural drawing. This scroll comprises illustrations accompanying ten songs from The Book of Songs as well as three prefaces. The calligraphy has been attributed to Gaozong, but the brushwork and character structuring suggest they could have been written by a copyist from the Imperial Academy of Calligraphy in imitation of the emperor’s style.

The present scroll passed through the collections of the Prince of Qianning and Qian Neng, a famous eunuch during the Ming. It was acquired by the Qing court during the reign of the Qianlong Emperor. In his colophon to this work, the Qianlong Emperor explained that Songs Beginning with “Deer Call” would serve as a model for the twelve Book of Songs scrolls in the imperial collection. These were later deposited in the Hall of Learning Poetry in 1770, followed by another two scrolls in 1784 and 1791. In 1922, the painting was removed from the Forbidden City by the last emperor, Puyi, who bestowed it upon his brother, Pujie. It was purchased by an antique shop in Beijing in the 1960s before it was returned to the Palace Museum.

Li Di (active 12th century)

Hawk on a Maple Tree Eyeing a Pheasant

Southern Song dynasty, 1196

Handscroll, ink and colour on silk

© The Palace Museum

This painting was signed and dated by Li Di, an artist whose work was highly regarded from the Yuan dynasty onward. Little is known about Li, except that he was a court painter who excelled in bird-and-flower painting.

Raptors hunting prey emerged as a popular subject for painting in the early Tang dynasty. When compared with other paintings on this theme, it’s clear that Li Di excelled in capturing motion and a sense of the spontaneous moment. This painting emphasises the reaction of the frightened pheasant, with the beaks, claws, and feathers of both birds depicted with remarkable precision and elegance that reflects the influence of highly naturalistic Northern Song painting. Tree trunks are delineated with saturated ink, while the leaves and grass are rendered in ink outlines and filled with colours. The painting is remarkable in ambition and scale—its enormous size suggests that it was originally mounted on a decorative screen.

The work likely influenced the paintings of the later periods, in which the hawk was used to represent dignity and independence. Once owned by Prince Yi of the Qing dynasty, it was given to the Palace Museum by the Bureau of Cultural Relics in the 1960s.

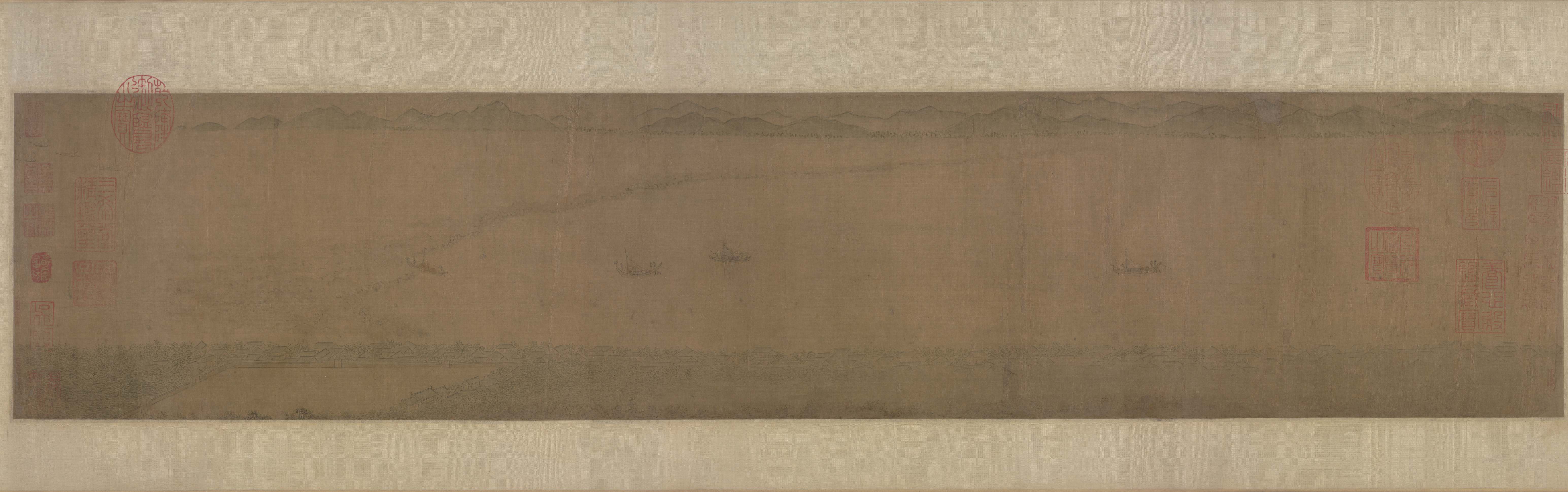

Li Song (1166–1243)

Viewing the Tidal Bore on the Qiantang River

Southern Song dynasty, late 12th or mid-13th century

Handscroll, ink and colour on silk

© The Palace Museum

Li Song, a native of Qiantang (present-day Hangzhou), was very familiar with the landscape and life along the river. The great finesse and realism of his figure, landscape, bird-and-flower, and ruled-line paintings earned Li Song a place in the Imperial Painting Academy during the reigns of three Song emperors, for which he received the sobriquet “Veteran Painter of Three Reigns”.

The present handscroll is one of the earliest extant paintings to celebrate the spectacle of the Qiantang River tidal bore—a phenomenon that occurs when the incoming tide forms a wave. Here, the painter captures boats hastening ashore as the river begins to swell and billow. On the near side of the river, in the foreground, the bank is lined by various architectural structures whose rooves peer through the mist, bringing to mind the prosperity of the Southern Song capital, Hangzhou. In the background, pale green washes define the sparingly delineated hills.

Lacking both a signature and an artist’s seal, the painting was attributed to Li Song during the late Ming dynasty. The handscroll bears colophons by Zhang Renjin and Yang Ji of the late Yuan and early Ming. It was in the collections of Ming collectors An Guo and Xiang Yuanbian, and Qing collector Liang Qingbiao, before entering the Qing imperial collection during the reign of the Qianlong Emperor. In 1922 the former Xuantong Emperor, Puyi, removed it from the palace and gave it to his brother Pujie. It was acquired by the collector Zhang Yuanzeng before it was returned to the Palace Museum in 1954.

Xie An (320–385)

Death of a Palace Attendant in Running Script (Song copy)

Guan Daosheng (1262–1319)

Late Autumn in Running Script (calligraphy by Zhao Mengfu)

Zhao Mengfu (1254–1322), Huang Gongwang (1269–1354), Xu Ben (1335–1380)

Calligraphy and Painting of Timely Clearing after Snowfall

Wu Zhen (1280–1354)

Fisherman